Federal regulators have receded from oversight of the buy now, pay later industry, leaving in their wake a patchwork of sometimes contradictory state laws.

The pullback by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which President Donald Trump and administration officials have vowed to dismantle, has created a trail of confusion. Now, state regulators are taking it upon themselves to consider overseeing BNPL players, with two passing their own laws.

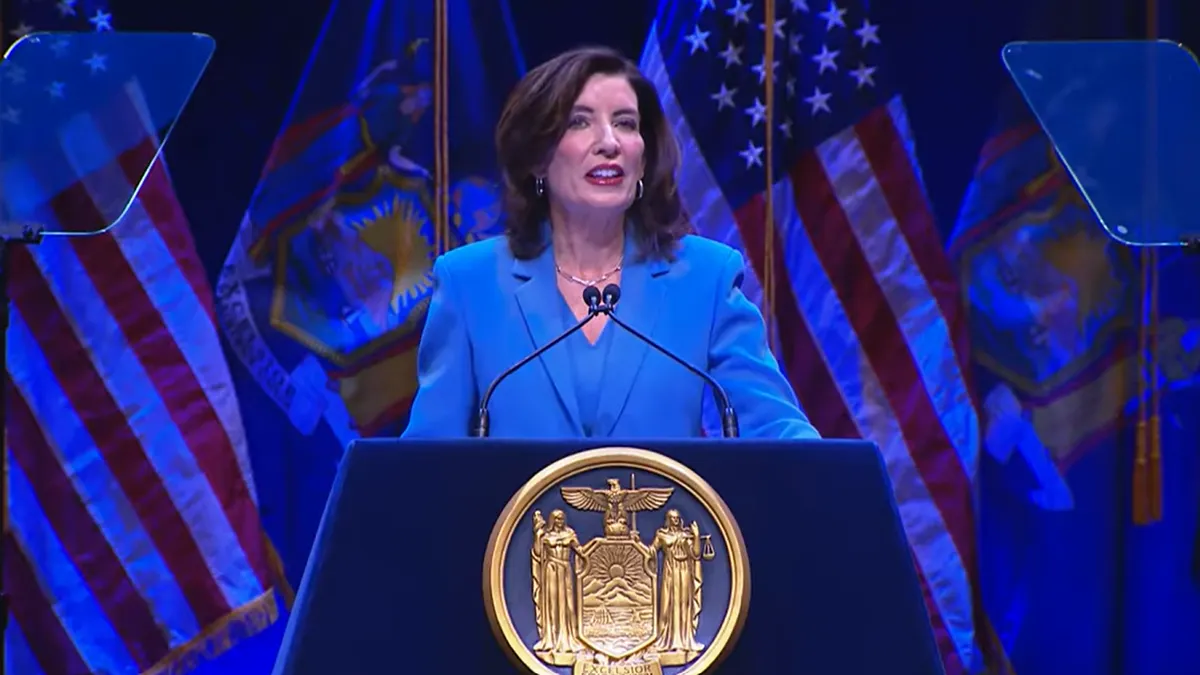

The new state laws have gone in opposite directions. While New York has taken an aggressive approach, Nevada has moved to smooth the path for buy now, pay later companies.

Most states have elected to regulate BNPL transactions under existing statutes related to payday lending and banking, but enforcement has been uneven, according to payments executives and industry consultants.

The percentage of consumers using pay later services has been on a steady incline, rising to 15% of those surveyed by the Federal Reserve saying they used the payment method last year, up from 10% in 2021, according to a May report on the survey results.

BNPL late payments on the rise

While BNPL companies have built their businesses on offering pay-in-four installment financing that may not require interest payments, they offer a variety of products, including loans that charge interest, just like traditional lending. That is further muddying the waters by putting pay later purchases under the purview of multiple consumer credit laws, said Crystal Kaldjob, an attorney at Goodwin Procter who is part of the law firm’s financial services group.

“Buy now, pay later is not just pay-in-four,” Kaldjob said in an interview. “It’s also longer-term, closed installment loans.”

While no U.S. statutes specifically mention buy now, pay later, the industry has oversight, stressed Penny Lee, CEO of the Financial Technology Association.

The FTA’s members include one of the largest BNPL players, London-based Klarna, as well as a smaller competitor, Zip. Other major players include Affirm Holdings, Block-owned Afterpay, PayPal Holdings and Sezzle.

“There are federal and state regulations that have been in place for a long time, and so BNPL products are regulated at both the federal and state level,” Lee said in an interview.

The patchwork of regulations for the industry is not unlike the litany of state and federal laws that govern traditional payment products such as credit cards, she said.

“It’s important to remember that financial services companies are highly regulated entities,” she added.

At Sezzle, CEO Charlie Youakim is closely monitoring state regulatory efforts, although Sezzle hasn’t seen a significant impact so far, he said, noting the New York law.

Trade groups representing BNPL providers, including the FTA, opposed the New York law this year.

The potential for onerous state legislation is one reason Minneapolis-based Sezzle is exploring whether to seek an industrial loan charter, a type of state banking charter that would let Sezzle become a direct lender.

Obtaining the charter would put Sezzle “one step further away from the fight” over state-level BNPL regulation, Youakim said in an interview. Sezzle may apply for the charter in Utah next year, Youakim said.

Such a charter would also be subject to approval by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Some states “try to overstep their rights,” Youakim said, again citing New York. He added that “a lot of the fintechs don’t have the coffers to fight a state.”

Changes at the federal level

Under Biden-era CFPB director Rohit Chopra, the federal agency unveiled an interpretive rule treating buy now, pay later purchases like credit card transactions, a proposal strongly opposed by many BNPL companies, who argued their products were an alternative to plastic.

Industry pleas found a receptive audience in the Trump administration. The CFPB’s interpretive rule on buy now, pay later from Chopra’s tenure was rescinded in May, just months after Trump took office.

“We observed in the tail end of the Biden administration what I would call recharacterizing types of products into categories that no one thought they would fit in before,” said Jason Cover, an attorney at the law firm Troutman Pepper Locke who has represented buy now, pay later companies.

Without federal regulations covering buy now, pay later purchases, it largely falls to the states to oversee the industry, and their approach has been anything but uniform. New York’s law takes a cue from the CFPB’s interpretive rule. That statute “essentially codified the same thing the CFPB had attempted to do,” Cover said in an interview.

Still, there are key differences between the bureau’s interpretive rule and New York’s law, Lee said. New York defines BNPL “very expansively,” she said. For example, “if you are in the lending business, even as a payment processor, you’re deemed to be a BNPL lender,” she added.

By contrast, Nevada’s law makes it easier for buy now, pay later companies to operate there by removing a requirement that they have a physical office in the state. Although the rule emphasized that pay later companies must comply with Nevada’s existing consumer lending laws.

How other states are responding

A handful of state attorneys general took action against pay later companies in the past five years without passing new legislation. “Many state AGs have signaled that they are worried about BNPL,” said Adam Rust, director of financial services for the Consumer Federation of America.

Those states include California and Maryland, which have specifically targeted BNPL companies for enforcement under existing laws.

Last year, Zip CEO Cynthia Scott said in an August earnings call that the company was not operating in Maryland because it lacked the appropriate license. The company was working to satisfy Maryland regulators so it could return to the state, a spokesperson for the Australian company said at the time. The spokesperson said this week that Zip is again offering its services in Maryland, but did not say when the company returned to the state.

Maryland last year also fined Miami-based BNPL Four Technologies — which gives retailers the capacity to offer pay-in-four installment loans — for offering lending services in violation of state law.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson for Maryland’s financial regulators referred to a statement the state made last year saying its lending laws are complex, with some pay later companies being required to have a license, while others aren’t.

“BNPLs are typically engaged in the business of making loans or extensions of credit,” Antonio Salazar, the state’s commissioner of financial regulation, explained in a Sept. 2024 email to Payments Dive.

In 2020, California made clear that pay later companies are considered lenders under state law. Since then Sezzle, Afterpay, Quad Pay and Four Technologies have all reached settlements with the state that allow them to keep offering there services there.

The state took legal action against pay later companies in at least two instances in 2020. Sezzle agreed to pay $300,000 in fines and loan refunds and Afterpay agreed to pay nearly $1 million in fines and refunds. Both companies agreed to acquire the appropriate license to provide loans in California.

State patchwork emerges

While BNPL companies have mainly marketed themselves as offering interest-free installment loans, which can be paid back over the course of a few weeks, the industry is increasingly offering longer-term, interest-bearing loans paid down over several months.

Affirm entered into a 2020 consent agreement with the Massachusetts Division of Banks to settle allegations it serviced loans in the state without the proper license. The company agreed to pay $2.25 million and to acquire a small loan license.

Five years later, the only other BNPL player to acquire such a license in Massachusetts is Klarna. A spokesperson for the Massachusetts Division of Banks did not respond to a message seeking comment.

Lending laws are not uniform from state to state. Some states require all lenders to be licensed, while others do only if the lender provides loans over a certain dollar amount or charges a specific interest rate.

Exceptions exist. Arkansas, for example, does not require any lenders to have a license, according to a rundown of state loan licensing rules related to BNPL by Bloomberg Law.

To add to the confusion, some states have laws regulating payday lenders, which may also cover buy now, pay later companies.

“If you’ve got a buy now, pay later product that charges late fees, charges interest, accepts tips, or withdraws money from a checking account on a certain day, that could fall under the payday lending statute,” said Matthew Lynch, chief legal counsel at Wisconsin’s Department of Financial Institutions.

Nonetheless, he is unaware of Wisconsin regulators taking legal action against any pay later companies, he said in an interview.

There are 37 states that have payday lending laws, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, although it’s not clear which of those statutes could also apply to BNPL companies’ services.

Ohio’s payday lending rules “do not contain anything related to buy now, pay later activity,” and the state doesn’t have any laws that govern BNPL loans, a spokesperson for the state’s Division of Financial Institutions said by email. Although when pressed, the spokesperson conceded that BNPL loans that accrue interest might fall under the state’s lending rules.

The agency has not taken legal action against any pay later players, the spokesperson said.

Some companies are still coming to terms with what states require. In Georgia, a handful of BNPL companies offer loans in partnership with a bank, and some have been confused about whether they needed a license, said Bo Fears, a spokesperson for the state’s banking authority.

State regulators had to remind several of those BNPL companies that they needed a license, he said. “If there’s a relationship where the bank makes the loan, but really the BNPL lender services it, they’re also required to have a license with us,” Fears said.

The uncertainty shouldn’t be a problem for the larger, established players, but will cause headaches for up-and-comers, said Nandan Sheth, CEO of Atlanta-based Splitit, a smaller industry player that lets consumers access installment loans with their existing credit cards.

“For new entrants, I think it becomes a little bit trickier,” he said in an interview. “I think they’ll either be a little bit more reticent to enter the market, or will use third-parties, such as federally regulated banks” to offer loans.

CFPB retreat creates federal vacuum

As states continue to consider how their lending laws apply to buy now, pay later transactions, problems will inevitably arise if state legislators and attorneys general prove less knowledgeable than their federal counterparts, said Susan Seaman, an attorney at the law firm Husch Blackwell who follows the payments industry.

“It’s important to remember that states’ definition of credit can be different than the definition and the scope of credit under federal law,” she said.

Any variance in the sophistication of state-level regulations “creates the risk of unintended consequences,” Seaman added.

In the meantime, shoppers may end up being the losers as BNPL use expands, consumer advocates like Rust say. The CFPB under Trump “decided to side with the fintech industry at the expense of consumers,” he said.

The proportion of consumers who make late payments on buy now, pay later installment loans has gradually increased as the payment method has become more popular. Of the 15% of consumers who used buy now, pay later last year, nearly a quarter made a late payment, according to the Fed’s survey.

That’s important, given patterns in use. Younger people and ethnic minorities are the most likely to use BNPL. According to the Fed’s survey, 19% of consumers between the ages of 18 and 29 have made buy now, pay later transactions, compared with just 8% of those over the age of 60. Meanwhile, 25% of Black consumers and 21% of Hispanic consumers have used buy now, pay later, compared to 11% of White consumers, the Fed survey said.

Low-income users paid late more often

This month, the Trump administration signaled the CFPB may shutter soon, after already shrinking its workforce earlier this year.

The bureau’s pullback comes at a time when the buy now, pay later industry is expanding by signing more partnerships with major retailers and e-commerce websites, Rust noted.

“Ultimately we know how that story ends up,” he said. “People get hurt.”

What does the future look like?

Some BNPL players expect there will be more state laws passed to regulate the industry in the absence of national rules.

While the patchwork may not get as confusing as the litany of state laws governing the earned wage access industry — which in the past few years has seen varying levels of regulation passed in statehouses — Sheth expects to see legislators across the country approve more buy now, pay later edicts.

“There will be state-level mandates," he said. "One-size-fits-all will not be the future.”

Sheth also predicts more banks getting into the pay later business in the absence of robust federal regulation.

"Big banks already have federal charters, they are already doing consumer lending, and they already have relationships with consumers," he said. “They also have a very robust risk management and compliance oversight to manage [buy now, pay later] programs."

For their part, consumer advocates continue to lobby for buy now, pay later purchases to be treated like credit card transactions, even as the industry vociferously opposes that course of action.

A state-by-state patchwork will never work as well as robust federal regulations, said Rust. “Is there a state that can match the CFPB?” he said. “I am not sure that there is.”

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas contributed to this story.