Louisiana has passed an earned wage access law backed by the industry while Connecticut’s governor must consider an option less popular with EWA providers.

In Louisiana, a bill outlining what EWA providers can do and the rights of consumers that receive services passed the Republican legislature and became law on July 1, without the Republican governor’s signature (that can happen after a certain period elapses). The new state law, which was backed by the industry, is set to take effect Aug. 1.

In Connecticut, where Democrats control the statehouse, Gov. Edward “Ned” Lamont, also a Democrat, must weigh a bill that is opposed by some earned wage access providers, partly because of what they say are “strict limits” on service fees.

Earned wage access has become a popular way for employees to access their pay before a regularly scheduled payday, but it’s also triggered controversy because workers may be subjected to fees. Dozens of EWA service providers, which include DailyPay, EarnIn, Flexwage Solutions and Chime, have voiced varying views about legislative proposals cropping up across the country.

Providers have an array of methods for providing the services, with some offering the payments through employers and others reaching out directly to consumers. They also have different revenue-generating models, with some exacting fees from users and others providing payment cards to workers and then sourcing interchange fees from merchants when the users spend.

Louisiana is now the eleventh state to impose EWA regulations, with 10 new state laws instituting oversight for the fast-growing fledgling industry since mid-2023.

Some states have opted for paths that focus on registering providers, among other provisions, while others have sought to implement stricter safeguards for workers, with some in between those paths.

Generally, providers and their trade groups, including the American Fintech Council, have supported a lighter regulatory touch, with licensing mandates for providers. Such legislation has been particularly successful in Republican-controlled states.

In Louisiana, the new law calling on providers to have policies for disclosing all fees to users; explain how users can complain about services; allow users to cancel services without a fee; and offer a no-cost option for services.

There are also parameters for how providers can seek payment of outstanding fees and that prohibit the sharing of any fees with a user’s employer. The provider also can’t receive payment of outstanding user fees by way of a credit card, or engage in false, misleading or deceptive advertising.

Importantly, the new Louisiana law states that EWA providers will not be considered lenders as long as they abide by the new law’s provisions. Whether state and federal lending laws apply to EWA has been a point of contention as policymakers debate how to regulate the young industry.

DailyPay praised Louisiana’s new law in a press release. “This new law will empower employees with real-time access to their earned wages and help businesses build stronger, more engaged workforces,” DailyPay’s Chief Legal and Strategy Officer Jared DeMatteis said in a July 2 press release.

Still, at least one EWA provider, FlexWage, sees the Louisiana approach as not well-suited to the task. The Louisiana legislators see their new law as an advantage for workers, but “they don’t put all the protection in there to make sure it’s an advantage,” FlexWage’s vice president of compliance, Carl Morris, said in an interview.

Morris and FlexWage have argued for more robust consumer protections for EWA users. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau had intended last year to implement federal regulations that would offer protections similar to those for lending, but those efforts are likely to be abandoned under President Donald Trump’s administration because it has essentially shut down the federal agency’s work.

In May, New York enacted a new EWA law that requires earned wage access providers to abide by the state’s consumer loan laws and institutes licensing regulations for such companies. Nonetheless, AARP, formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons, opposed the legislative proposal early on, arguing in a press release that it would subject low-wage workers, who the association says are often older people, to “predatory financial practices and excessive fees.”

There have also been concerns raised about the practice of users “stacking” their EWA disbursements, incurring mounting fees, Morris said.

On the flip side, the Connecticut bill has prompted negative comments from the industry, partly because the legislation doesn’t differentiate EWA services from traditional lending.

In a letter to Lamont last month opposing the Connecticut bill, the American Fintech Council as well as two top executives from DailyPay and EarnIn complained that the pending legislation inappropriately limits fees to $4 per transaction and caps them at $30 per month for a given user.

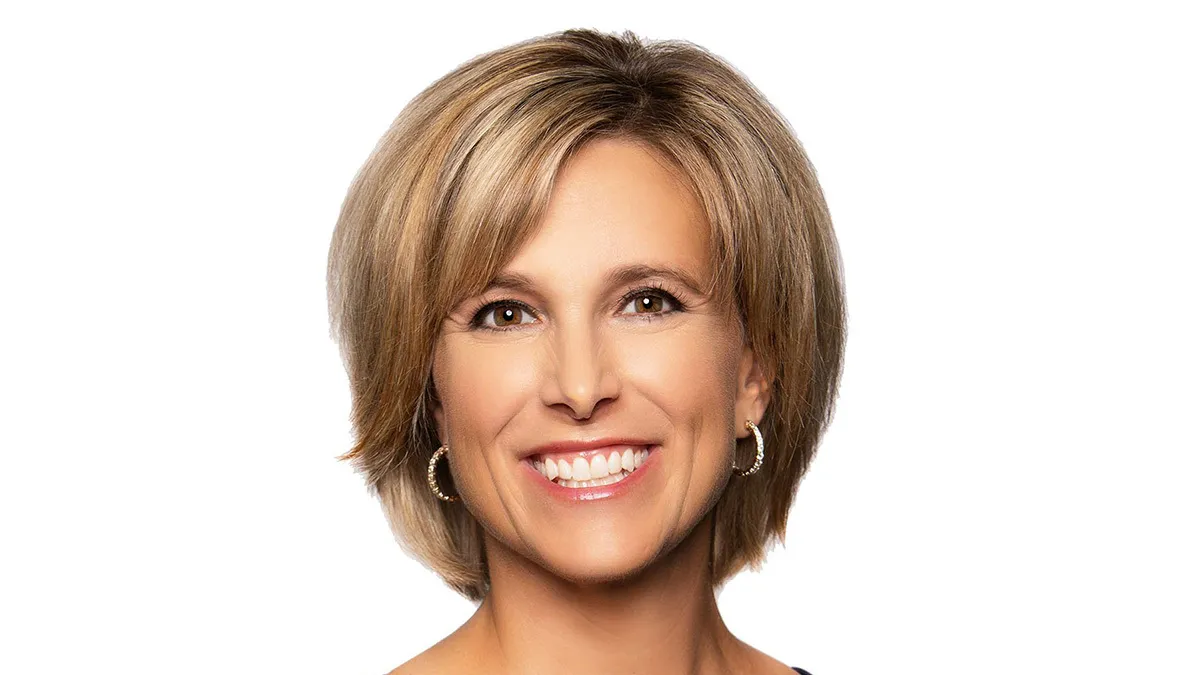

“These proposed caps on EWA fees are stricter than any others enacted within the United States, and likely below the fully-burdened cost of operation for many providers,” said the June 25 letter, signed by AFC CEO Phil Goldfeder; DailyPay CEO Stacy Greiner; and EarnIn CEO Ram Palaniappan.

The letter writers also dinged the bill’s requirement that EWA providers offer at least 75% of a worker’s earned and unpaid wages for a pay period, saying it will unfairly preference the largest EWA companies.

The provisions could force some EWA providers to limit their services in Connecticut, or to not make them available in the state at all, the letter said.

“Regardless of whether he signs, we are already looking forward and planning for the legislative session in 2026 to work on a new bill that will enable thousands more (Connecticut) families to take advantage of this vital financial service,” Goldfeder said by email on Monday.