Jason Lee is the chief of enterprise at neobank Chime, and the founder of fintechs DailyPay and Salt Labs.

Ten years ago, earned wage access (“EWA”) start-ups had the courage to change a century-old pay system. By converting raw, unaudited human resources information system data into a digital earnings balance, EWA enabled workers to view and access their pay in real-time.

It quickly became its own human capital management category, offered by thousands of companies to millions of workers. I am grateful to have co-founded and led one of the original EWA companies until 2022.

Yet, many employers remain on the sidelines for two reasons: cost and compliance. They’re concerned with cost because many workers have become chronic EWA users, racking up hundreds of dollars in annual fees. And they’re concerned with compliance because EWA implicates financial, labor, and tax rules. Exhibit A is the New York Attorney General’s lawsuit against two EWA providers for violating usury and other state laws.

There are two potential industry responses to these challenges: (i) it can change its model to conform to the rules, or (ii) it can change the rules to conform to its model. The industry has taken the latter approach through bills, petitioning, and PR.

These efforts have resulted in 11 state EWA laws that exempt providers from some combination of lending, money transmission, wage assignment, and wage deduction rules. But these states represent only 15% of the U.S. population. What about employers in the other 85%?

If EWA companies embraced the same innovative spirit that led to the industry’s creation, we could have free and universal access to wages. I am seeing the beginnings of this internationally with a few providers taking this approach. Domestically, I hope to “be the change you want to see in the world” to usher in this new era of EWA.

I agree with Brian Tate, who is CEO of Innovative Payments Association, that “Americans living paycheck to paycheck deserve better” when EWA is threatened by regulations. But the industry response should be to change its software code, not the regulatory code.

This industry simply cannot continue to charge employees to access their pay. We cannot expect employers to deduct these fees from paychecks through payroll. And we cannot expect 50 state finance and labor regulators to unanimously approve of this. California has cited APRs of over 330% while the New York AG has warned of “cycles of dependency [that] have the potential to wreak financial havoc on individual employees’ lives.”

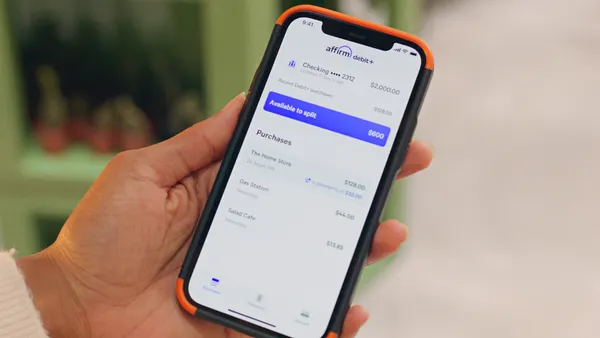

It is indisputable that workers should have access to their pay. Period. But that is very different than paying for your pay. At its best, EWA can be a first step to financial progress. When paid at a more regular cadence, hourly workers are better equipped for longer-term financial planning and more inclined to put money away, so long as they aren’t penalized for accessing their money.

This is all very simple: the optimal EWA approach is the one available to the most people at the lowest cost. Technology advances now make it possible to offer a fully compliant and completely free service that graduates users into savers. When EWA was invented, bank overdraft fees cost $35; now some financial institutions offer it for free. It’s time that EWA moved into its next stage of evolution as well.